A fiction allows one to see the truth and also what it hides.

Marcel Broodthaers

The art museum is a complex structure that has been evolving for centuries, starting with the emergence of the kunstkammer and wunderkammer in the 16th century; encyclopedic collections of diverse objects that attempted to purvey a vision of the world. These cabinets usually belonged to the wealthy or the aristocracy, whose economic power made possible the accumulation of rare objects and works of art. They paved the way for the formation of royal collections, which –during the social and political upheavals of the end of the 18th century, and specifically the French Revolution—became the first public museums. The ontological shift brought about by the creation of the Musée du Louvre in Paris from the royal collections –one that marked the shift from the king’s picture gallery to the peoples’ museum—as well as the epistemological ruptures of the Enlightenment, such as the development of the exact sciences and taxonomic systems, oriented museum practices towards the public sphere and conceived of a social function for museums. Nowadays there exists a variety of institutional models; from the state museum, born out of the French Revolution, to the private, corporate-like, model, sustained by private boards and individuals, which prevails today in the United States.

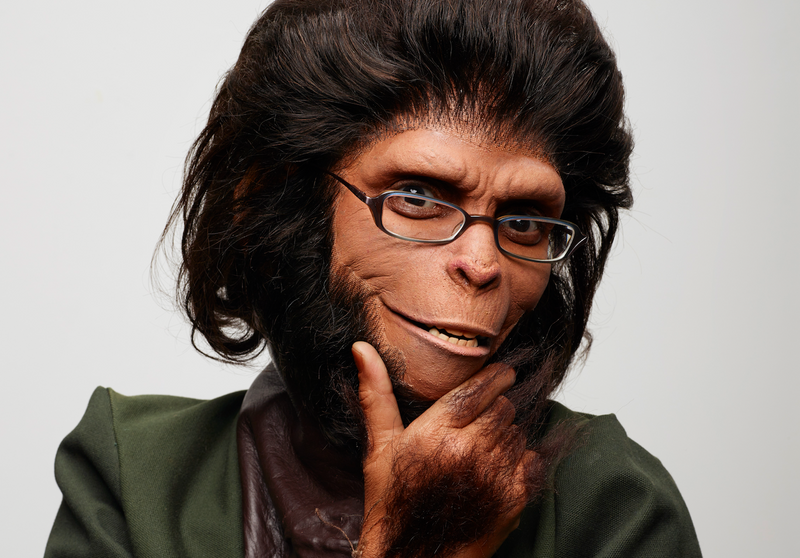

During the twentieth century the museum as a structure of knowledge, as well as its classificatory strategies, became the subject of interest for many artists who appropriated the idea of the museum. Some embraced the arbitrariness of the cabinet of curiosities as a poetic form; one that in its heterogeneity offered a singular freedom that the disciplined and ordered model of the museum did not. Notable examples in the history of post-war art include: George Maciunas’ Flux Cabinet; Robert Filliou’s, La galerie légitme, an art gallery in a hat; Claes Oldenburg’s Mouse Museum; and perhaps the most radical of all, Marcel Broodthaers’ Le Musée d’Art Moderne, Département des Aigles (The Museum of Modern Art, Department of Eagles) which existed under various incarnations and in several locations, including art fairs, between 1968 and 1972.

Broodthaers’ museum expanded the horizon of the museum towards the intersection between art and the market, in an acknowledgement of its inexorable transit towards capitalist modes of production and exchange. Originally a poet, Broodthaers decided to become an artist in 1964, motivated by the thought that he could “sell something and succeed in life,” thus “the idea of inventing something insincere” crossed his mind, and he set to work at once… Likewise fiction was for Broodthaers part of this agenda of “insincerity” that he deployed in his museum and its different incarnations, where the exhibited objects were marked by numbers with a note that designated their condition: “this is not a work of art.” The financial mechanisms of institutions, such as fund-raising, deaccession, and commercial exchanges that are part of the workings of private museums today, were also parodied in advance by Broodthaers with the creation between 1970 and 1971 of the Section Financière (Financial Section) of his museum. There, Broodthaers announced a campaign to raise funds with gold ingots stamped with the figure of an eagle, the value of which was duplicated due to their added value as works of art; later, he placed the museum on sale, due to bankruptcy (à vendre pour cause de faillite).

This exhibition that presents itself as the idea of a museum, thus a fiction, organized in taxonomic divisions—orders—that simultaneously support but also interrogate this regime of classification, locates itself within a wide universe of referential coordinates that transcend Broodthaers’ gesture. Nevertheless, it also operates within the conceptual register articulated by Broodthaers, particularly in what regards the tensions between art and the market. In tracing an “evolutionary line” between homo faber and homo economicus, the exhibition highlights the forces that exert an influence on the museum’s modes of representation today. The “natural order of things” of late capitalism that is referenced by the film The Network, and which gives title to the exhibition. The fictional museum inscribed, physically and conceptually, within Museo Jumex has its own regime of representation, identity and architecture. Within each “order” a conversation is generated among works and texts quoted from different sources. Outside its Palladian floor plan there are works that allude to art, from its early definition as mimesis in Greek classical Antiquity, the museum as a form of knowledge, representation, and classification. In a certain sense, these works configure an order of orders, or a meta-order, that builds a discursive platform from poetic points of inflection provided by the works and their particular ways of addressing the concepts of art, museum, and representation.

This exhibition serves a double purpose; aside from offering a reflection on the idea of the museum and its modes of representation to our publics, it also presents the particular approach to the contemporary taken by Museo Jumex’ curatorial department in its current and future program. An approach that reflects the desire of artists to seek fields of agency outside the boundaries of the institutional-gallery framework and the art-historical canon, and that identifies, culture, the built environment, the flows of capital and information, as well as the intersection between art and life, as important discursive arenas in contemporary art practices. Furthermore, it offers the public an insight into how our curatorial team is approaching the Jumex Collection and how this resource allows us to generate different curatorial formats and ways of working.

It all started a 17th of January, one million years ago. A man took a dry sponge and dropped it into a bucket full of water. Who that man was is not important. He is dead, but art is alive. I mean, let’s keep names out of this.

Robert Filliou, Whispered History of Art

- Artschwager, Richard

- Levine, Sherrie

- Klein, Yves

- Calderón, Miguel

- Halilaj, Petrit

- Lawler, Louise

- Orozco, Gabriel

- McCarthy, Paul

- Abaroa, Eduardo

- Glassford, Thomas

- Ortega, Damián

- Hopper, Dennis

- Pettibone, Richard

- Judd, Donald

- Koons, Jeff

- Chicago, Judy

- Höller, Carsten

- Durant, Sam

- Ligon, Glenn

- Rennó, Rosângela

- Baldessari, John

- Kawara, On

- Zittel, Andrea

- Lichtenstein, Roy

- Williams, Christopher

- Vaisman, Meyer

- Sinister, Dexter

- Simmons, Laurie

- Sierra, Gabriel

- Sarabia, Eduardo

- Shrigley, David

- Smith, Melanie

- Smith, Kiki

- Superflex,

- Rossell, Daniela

- Ruff, Thomas

- Reyes, Pedro

- Panayiotou, Christodoulos

- Torres, Rubén Ortíz

- Okón, Yoshua

- Metinides, Enrique

- Matta-Clark, Gordon

- Mach, David

- Morris, Sarah

- Monk, Jonathan

- McCracken, John

- Macchi, Jorge

- Leavitt, William

- Lara, Adriana

- Lockhart, Sharon

- Knowles, Christopher

- Kippenberger, Martin

- Kelley, Mike

- Kuri, Gabriel

- Jankowski, Christian

- Johns, Jasper

- Iturbide, Graciela

- Covarrubias, HCRH y Jorge

- Herrera, Arturo

- Horowitz, Jonathan

- Höfer, Candida

- Hirst, Damien

- Gilligan, Melanie

- Graham, Dan

- Gillick, Liam

- García Torres, Mario

- Gaillard, Cyprien

- Fusco, Coco

- Feldmann, Hans-Peter

- Dragset, Elmgreen &

- Dzama, Marcel

- Curtis, Adam

- Camacho, Christian

- Deball, Mariana Castillo

- Calder, Alexander

- Chamberlain, John

- Cattelan, Maurizio

- Cuevas, Minerva

- Cruzvillegas, Abraham

- Borja, Santiago

- Bulloch, Angela

- Beshty, Walead

- Almond, Darren

- Amorales, Carlos

- Alÿs, Francis

Exhibition organized by: Julieta González and José Esparza Chong Cuy

Curatorial assistant: Ixel Rión

Architecture: Pedro&Juana

Graphics: Dexter Sinister